Written by: LesLee Clauson Eicher and Ann Koenig, AACRAO International

What do you do when the educational system reflected by the secondary education documents you are looking at doesn’t match the system of the country where the school is located? If you are responsible for evaluating documents from secondary schools in other countries, read on! This article is based on an international admissions training module developed by the authors. We hope that this article will help you to identify some of the principles of best practice in applied comparative education, apply those best practice principles to the evaluation of secondary education, and enhance your skills in researching secondary education.

For international credential evaluators, it’s becoming increasingly common to see academic documents from secondary schools that are not a part of the educational system of the country in which they are located. Their presence may be a physical one: a brick-and-mortar school. Or it may be a school that imports or exports its curriculum. Or something in between, a hybrid that teaches a foreign curriculum alongside a local curriculum.

ISC Research, a British organization that keeps statistics on international schools world-wide, reports that there are currently 8,789 international schools around the world. Nearly five million students attend them, and 444,323 staff are employed at these schools. The schools bring in over forty billion dollars per year. In just five years, from 2011 to 2016, the number of K-12 global international schools rose nearly forty-three percent. See here more information.

With such a growing presence, it’s inevitable that credential evaluators who work with secondary-level credentials are going to encounter documents from one or more of these models of international schools. The number of models, the varied missions of the schools, myriad country-combinations, and the variety of leaving-certificates awarded all complicate the analysis process.

Consider the example of the Senegalese-American Bilingual School in Dakar, Senegal. Reviewing a “12th Grade Yearly Recapitulation of Grade”, we see that it is issued in English and shows some characteristics of US high school education, such as the terminology “completed all of the requirements for high school graduation”, notations of “Advanced Placement” subjects, references to “Brigham Young University” for some subjects, and “Carnegie units” for subject credits. So is this school American? Or Senegalese? Or both? And what does “bilingual” mean? Who is this school intended to serve? What is its mission? Is this school “recognized” in Senegal? Is there any North American organization that quality assures it? What options for higher education do its graduates have?

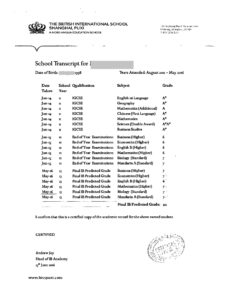

Another example is The British International School in Shanghai, Puxi, China. A School Transcript issued in English for a student enrolled in “School Year 13” in 2016 lists British IGCSE (International General Certificate of Secondary Education) subjects for School Year 11, “End of Year Examinations” subjects at “Higher” and “Standard” levels for School Year 12, and “Final IB Predicted Grade” subjects in Year 13. The school is called a “British” school, but after Year 12, is it still the British secondary system at work? What does “End of Year Examinations” refer to? And how does the 12-year “IB” program fit into Year 13? Is this school recognized in China? To what types of further education is a graduate of this school going to have access?

These two examples reflect transnational secondary school models that commonly cross credential evaluators’ desks around the world. There are many variations on this theme.

For instance, the school in question:

- Might not belong to the educational system of the country in which it is located

- Could be a school that is a – you fill in the blank with a national adjective – “Canadian / French / American / Turkish, etc.” – school located outside of that country

- Could be accredited by a US regional accreditor but isn’t located in the US, or could be accredited by some other accrediting organization in a different country

- Could possibly be a government-funded or private school that calls itself an “international school”

- Might be a religious school that teaches a denominational curriculum across the world

- Might be an “IB school”, teaching the International Baccalaureate curriculum, which doesn’t belong to any country

- Could be an “A-level college” run on a British model, an imported curriculum, outside of Britain

- Might be a school for refugees from another country

How does each of these work? In some cases, the schools offer their own country’s curriculum in a physical school in a foreign country, not only to expatriates, but to citizens of the foreign country as well. This type of model could be called an “international school,” a “[name of country]school,” or go by another name.

Some schools may purchase or subscribe to a non-indigenous curriculum and offer it locally. This model, as exemplified by the British IGCSE (International General Certificate of Secondary Education) or GCE A-Level (Advanced-Level) model, is perhaps the most widespread around the world.

In some countries, one might find a school offering the curriculum of a foreign country to its expatriates living abroad, as well as to locals, but due to government regulations in the host country, the school must also be required to offer the indigenous curriculum alongside the foreign one. In some cases, students might be required to fulfill the requirements for the host country’s secondary school leaving credential, as well as the requirements for the credential given in the foreign system.

And then there are the curriculums that are not indigenous to any one country, and that are offered in any school in any country that chooses to subscribe to (purchase) and offer the curriculum. “IB (International Baccalaureate) schools” would be an example.

Given the variety of models of transnational and international schools, how do we evaluate these schools and their programs? The answer is: We follow the same principles and methodologies we employ when evaluating postsecondary education.

Principles of best practice in applied comparative education require us to find the answers to these questions:

- Where is the school located? (We’ll call that “Country of Location”.)

- Who runs the school? Is it part of the government-funded educational system or a private entity? If private, is it operating legally or legally recognized? Who quality assures it? (We’ll call that “Legal Status”.)

- What does the school teach? Who are its students? Are they headed for higher education in the Country of Location or somewhere else? What curriculum content will they need to achieve their goals? Is it the curriculum that is taught in public schools in that locality? If not, what is it? (We’ll call that “Type of School / Curriculum Offered”.)

- Is the completion credential awarded at the school legally an indigenous credential? Is it legally valid in another country? Who regulates the validity of the completion credential? (We’ll call that “Graduation Credential”.)

- What options for further education are available to the “Graduation Credential” holder? (We’ll call that “Access to Further Education”.)

- What does the school say about itself? Where can the evaluator find reliable, accurate information to confirm the information? (We’ll call that “Resources”.)

To answer all of these questions, an evaluator needs to rely on his or her knowledge of the educational system of the country of the school’s location, as well as be able to recognize clues in the documentation. Many transnational or international schools have Web sites to provide parents, guidance counselors, admissions offices, and the local community with the information noted above, especially if the school is not part of the local education system. The school’s Web site can be a valuable starting point for research. Using the documentation and reliable credential evaluation resources, the evaluator should confirm factors such as the curriculum taught at the school, benchmarks in that system, terminology, grading scales, and recognition bodies, and then apply standard credential evaluation methodology.

Now let’s look at the details of each components to be examined in the evaluation process.

Country of Location:

- Where exactly is the school located?

- If it is an online school, where is the school legally registered to operate? Under what legal jurisdiction in what location?

- Is the school operating in its own country, but offering a different country’s academic curriculum?

- Is it a school operating in a foreign country, that is, a country other than the one whose curriculum it teaches?

- Is the school part of a network offering instruction in many locations, such as a refugee program sponsored by a non-governmental organization, or a religious denomination that runs schools all over the world?

Legal Status of the School:

- What is its legal status vis-à-vis the public education authority in the legal jurisdiction in the Country of Location? Is the school public (government-funded), private (privately-funded), or something else, possibly a hybrid?

- Does the public education authority allow private education providers?

- If so, is the school authorized as a private education provider?

- If not, what is its status? Is it operating with a status that allows it to offer private education legally?

- Does it have recognition / accreditation in another country’s system? If so, what type of recognition / accreditation?

Type of School / Curriculum Offered:

- Who is this school intended to serve? What type of school is it?

- What type of curriculum does the school offer? The indigenous one in the educational system of the locality? A non-indigenous one? Both?

- Does the school offer a curriculum from a non-national entity, such as IB or a transnational curriculum provided by a religious denomination?

- If more than one curriculum is offered does the school offer students/parents a choice?

- For the curriculum completed by the person whose credentials you are evaluating, what are the key elements of the curriculum that you need to know for evaluation: structure (school year, content, use of quantitative measures such as credits or units, assessment methods/grading, requirements to earn the “Graduation Credential”)?

- What is the structure of the system of which the curriculum is a part (level of the education, number of years, benchmarks, access to further education)?

Graduation Credential:

- What is the name of the “Graduation Credential”?

- Is it the same “Graduation Credential” earned by students in the indigenous system of the “Country of Location”?

- If not, is it a recognized “Graduation Credential” in another country or system of education?

- Does the student receive more than one “Graduation Credential” for completion of one curriculum?

Access to Further Education:

- Does the “Graduation Credential” give access to higher education in the country in which the school is located? Is it an indigenous credential or is it a “foreign” credential?

- Does it give access to higher education in the country whose educational system it comes from, as a native credential, or is it a “foreign” credential?

- For admission to your institution, are there be additional factors that you would look for to determine whether the “Graduation Credential” meets your requirements?

Resources:

- What does the school say about itself? Does the school have a profile sheet? Is the information accurate? (How do you determine if it’s accurate? Is there information online? Is it official? Trustworthy?)

- What kinds of official and reliable resources would you need to consult in order to confirm information about the legal status, curriculum offered, graduation credential and access to further education?

An Example: The Senegalese-American Bilingual School (SABS)

Now let’s ask these questions of our first example, The Senegalese-American Bilingual School (SABS). On the basis of our research, we have some answers, but have also identified some further questions.

Country of Location: Senegal

Legal Status: SABS opened in 1993 as a preschool with just a few students. According to documentation obtained from the school by the EducationUSA advisor at the US Embassy in Dakar, Senegal (https://www.educationusa.state.gov/), in 1994 the school received authorization from the Senegalese Ministere de l’Education nationale (http://www.education.gouv.sn/root-fr/files/index.php ) to operate as a private institution in the Senegalese educational system. It offered primary education (“primaire”, years 1-6) and in 2008 was authorized to extend its offerings to “moyen complet” (4 years) and “secondaire complet” (3 years). The school is authorized to award the Senegalese Baccalauréat in the L and S streams. In the ministry legislation, the school is called “Le Petite Ecole Bilingue”.

Type of School / Curriculum Offered: The school draws American, Senegalese and other families who wish their children to have a bilingual education and prepare for higher education.

- Evaluator questions: American? Senegalese?

-

- How how do the American-style courses shown on the transcript relate to the indigenous curriculum taught in Senegalese public schools?

- The transcript shows “Carnegie units” and percentage grades with a concordance to a letter grade, not co-efficients and a 20-grade scale as we would expect to see from a Senegalese school. Where do the units and grade scale come from?

Graduation Credential: Baccalauréat, L and S streams

- Evaluator question: The 12th grade transcript states that the requirements for “high school graduation” have been met. Does the graduating student receive a US-style high school diploma, or a Senegalese Baccalauréat, or both?

Access to Further Education: The school profile lists several institutions that have accepted graduates of SABS.

- Evaluator question: On the basis of which credential have institutions outside of Senegal accepted graduates of SABS? Do graduates present the Senegalese Baccalauréat?

Resources consulted for information about SABS:

- Ministère de l’Education nationale (Ministry of National Education): http://www.education.gouv.sn/root-fr/files/index.php.

- AACRAO EDGE Senegal profile: http://edge.aacrao.org/country/overview/senegal-overview

- EducationUSA Senegal, advisor at the US Embassy in Dakar: https://dakar.usembassy.gov/resources/education-advising-service.html. Was able to contact the school directly and obtain a copy of the legislation authorizing the school and the school profile sheet.

- Interview with school founder and director, Stephanie Kane, in The PIE News: https://thepienews.com/pie-chat/stephanie-nails-kane-sabs-senegal/. Includes background and history of the school.

The same process of analysis should be applied to the documentation from the British International School in Shanghai, Puxi, China, and other schools for which it is not clear at first glance at the transcripts “whose system is it, anyway?” We hope that what we have outlined here will help you to identify some best practices in credential evaluation and apply them to evaluating secondary education, especially in the cases of schools whose status in the country in which they are located is not clear cut or may be complicated to discern. As the number of these schools increases, it behooves evaluators who work with secondary-level documents to become familiar with the approaches we have presented here.

- Using trusted resources, confirm the location of the school, the legal recognition authority for that location, and the status of the school. To whose system does it belong?

- Use clues in the documents to help you.

- Confirm the completion credential and what it gives access to.

- Check information provided by the school. Save useful information in your resources file.

- Apply your institutional admissions policies.

- If you have several students from the same school, track their progress.

RESOURCE COLLECTIONS COUNTRY-BY-COUNTRY IN ENGLISH FOR EVALUATING SECONDARY EDUCATION

The following resources focus specifically on information about elementary and/or secondary education.

1) UNESCO International Bureau of Education (IBE), World Data of Education 2010/11 (data from the ministries of education): http://www.ibe.unesco.org/en/services/online-materials/world-data-on-education/seventh-edition-2010-11.html

IERF Index of Secondary Credentials (2010): http://www.ierf.org/for-institutions/ierf-publications/index-of-secondary-credentials/

2) NAIA International Academic Published Standards: https://www.playnaia.org/page/intldirectory.php

NCAA International Standards: http://www.ncaapublications.com/productdownloads/IS1516.pdf

3) UK UCAS International Qualifications for Entry to University or College (in the UK), 2015: https://www.ucas.com/sites/default/files/2015-international-qualifications.pdf

Inside this edition:

President’s Welcome: November 2017 Newsletter

Committee Updates: November 2017 Newsletter

Education and Licensure of Health Care Professionals in the USA: November 2017 Newsletter

Memoriam to Sandy Gault: November 2017 Newsletter

TAICEP Elections: November 2017 Newsletter

TAICEP Strategic Plan: November 2017 Newsletter

TAICEP News: November 2017 Newsletter

Add to Your Library: November 2017 Newsletter

Recent TAICEP Events: November 2017 Newsletter

Upcoming TAICEP Events: November 2017 Newsletter

From the TAICEP Website: November 2017 Newsletter

Notes from the Field: November 2017 Newsletter