Written by Peggy Bell Hendrickson, Director, Transcript Research

Welcome back to the ongoing series on Building a Resource Library. In earlier articles in this series, I discussed the importance of building your own in-house resource library. Essentially, it doesn’t help you to have wonderful, useful information if you aren’t able to find it when you need it. The next article in this series focused on one method for organizing that data: a web-based database known as a wiki where you create and manage the content. The most recent article in the series focused on the importance of expanding your samples library and included numerous resources for tracking down and collecting samples. This article focuses on another layer of resources: namely, languages. In particular, I am referring to how you handle academic credentials that are issued in a language that you can’t read.

Obviously, there are going to be many times when reading the documents in the native language is simply not an option, due to time, limited glossary resources, or simply lack of experience. What can you do if you don’t read the language? The most obvious response is to have the student provide a translation. It’s important to note that not all translations are created equally. I’ve come across many translations that were… generous, to put it mildly. Sometimes, translators try to help by interpreting what’s been written rather than simply translating from another language to your language. Instead of listing a grade in the native grading system, they will attempt to convert it to your grading scale for you, but they may not use the same grading scale conversions you use. Some translators try to help you determine the equivalency of a credential via the translation. I’ve seen a number of 2-3 year technologist diplomas translated as Bachelor of Technology.

Sometimes cognates can throw you for a loop as well. It’s very common for both Bachiller and Baccalaureat to be translated as Bachelor, for example, even though it is a high school leaving credential in many Spanish- and French-speaking countries. It’s important for you as an evaluator to understand the native language terminology for the specific country of the documents as well as how those credentials fit within the educational system as a whole. Relying on a translation for either or both of those elements will put you in a position of potentially admitting or hiring an unqualified student.

On the other hand, translators can simply make mistakes, such as typographical errors, transposing numbers, omitting a subject or semester, and other unintentional mistakes. Translations are frequently incomplete, focusing on the elements that the translator (or student) think are important such as the graduation information or course listing and leaving off other critical elements on the native language documents such as entry requirements, grading or passing system, portion of coursework completed, or other information that might assist you in your assessment of the student’s abilities. I’ve also seen translations that have removed failed grades or mislabeled clearly-identified developmental coursework. Sometimes translations may freely switch between words like university, institution, academy, college, and other educational institutions, so sometimes researching an institution’s recognition is complicated by the differences in how the institution’s name is translated. The same goes for determining equivalencies based on translations rather than native language graduation documents.

By relying exclusively on translations, you also miss out on the really neat security features that many institutions are embedding in their official documents. While increasing numbers of universities and secondary leaving examination boards are providing digital methods of verifying their documents, there are still more physical documents than electronic records, so it’s important (and fun!) to learn about the variety of security features in official native language documents.

My philosophy about translations is pretty simple: the more you have to rely on the translation, the more professional – and distant from the student – it should be. What does that mean? If you or others in your office can read the native language documents (at least well enough to check the translation for accuracy), then you might not be as particular in your requirements for who does the translation. You may even allow the student or a family member to translate because you can read the documents but simply don’t have the time yourself to translate them. On the other hand, if you have to rely heavily on the translations, it’s critical that the translation be removed from the applicant, either by having it done in-house or having it done by a reputable external translator, such as a certified translator in the home country or in your country. In the US, the American Translator’s Association is a professional association of translators and interpreters that requires a certification examination for professional translators to ensure that the translation is an unbiased, professional, quality, and dependable translation. The ATA is a member of the Federation International des Traducteurs (International Federation of Translators), which includes more than 100 professional translations associations and would be a good place to start if you want to find a reputable translation organization in your country.

I’ve been talking about translation, which is essentially converting from one written language to another. An interpreter is someone who translates spoken words, and a translator does the same for the written language, allowing you to read the words in your own language. Another common term in our industry is transliterate. How is that different from translate? Transliteration is converting the individual characters from one alphabet into the characters or letters of your own alphabet with the intention of letting you approximate the pronunciation of a word in your own language.

| Language | Native Term | Transliteration | Translation |

| Chinese | 专科 | Zhuanke | Undergraduate Non-degree Study |

| Chinese | 本科 | Benke | Undergraduate Degree Study |

| Chinese | 硕士 | Shuoshi | Master’s Degree |

| Cyrillic | бакалавра | Bakalavra | Bachelor |

| Cyrillic | специалиста | Spetsialista | Specialist |

| Cyrillic | магистра | Magister | Master |

| Persian | کاردانی | Kardani | Associate |

| Persian | کارشناسی | Karshenasi | Bachelor |

| Persian | کارشناسی ارشد | Karshenasi-Arshad | Master |

| Arabic | شهادة | Shahada(t) | Diploma |

| Arabic | البكالوريوس | Albukalurius | Bachelor |

| Arabic | ماجستير | Majister | Master |

Why am I talking about transliteration in a written document if transliteration is supposed to focus on the pronunciation? Some of the resources that we use in order to learn about an education system include transliterations of the indigenous documents or terms rather than the names in their native language. This is especially common for languages that use an alphabet that differs tremendously from the alphabet of the education resource. It is often difficult to know if the native language document you are working from is the right document or the credential mentioned in your resources when some of the country resources use the native language terminology and others use the transliteration.

I don’t know about you, but I’m not a polyglot. I’ve taken a few years of a few languages and have learned a smattering of “transcriptese” in several more, but I was relying more on translations than I care to admit before I decided to make it a priority to learn to read native language academic credentials. Obviously, this is easier for those languages whose alphabets are similar to the alphabet of my own language. For example, Romance languages (also known as Romanic languages or Latin languages), or modern languages that had a common origin in Latin, generally have a similar alphabet since they have their basis in the same Latin alphabet. As a result, the spoken languages may sound totally different from one another, but the written languages of Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian, and French – the five most widely used Romance languages – share many similarities.

This makes it much easier to examine the native language documents from other Romance languages if you already have an understanding of one of them. While English is not a Romance language – it’s technically a Germanic language due to the basic structure – many, many English words are borrowed from or influenced by Romance languages. English and Romance languages (and Germanic languages) all use various adaptations of the Latin alphabet, which also helps simplify the process of figuring out which words need to be translated and added to your in-house glossary. Even if you’re not able to read the document, the similar alphabet makes it much easier to search for a translation.

But even for those languages that you or your staff don’t read, there are a number of strategies for working as much as possible with native language documents.

- Look for patterns in the graduation documents and transcripts

- Learn to read degree names, degree categories, and other relevant common terminology

- Learn to read numbers

- Learn to read grades in the native terminology

I’ll discuss each of these steps in greater detail in the paragraphs below.

Look for Patterns

Initially, my plan to learn to read native language credentials stemmed from noticing that some countries have uniform graduation credentials. While I knew that reading the entire transcript would be beyond my nascent skills, I could certainly learn to identify standard patterns that appear on all of the credentials for a given country. Actually, you can start even smaller than focusing on an entire country. Learn to recognize the patterns to read a single qualification that you see regularly. Have verified samples that you can study and compare against.

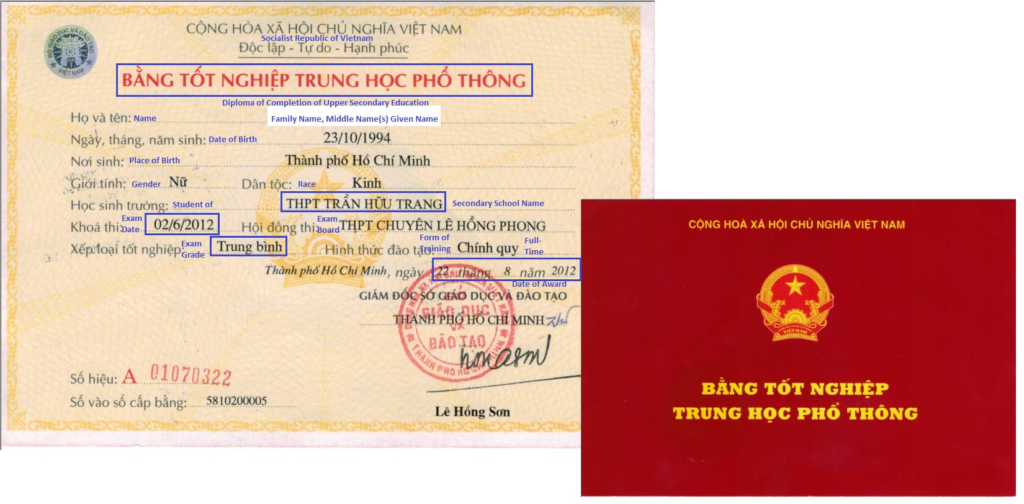

Before I was even conscious I was doing it, I was “reading” native language secondary school diplomas for countries where the diplomas are issued by the Ministry of Education. Being issued by a central body (examination board, Ministry, single degree-granting university, technical council, etc.) increases the likelihood of standardization, which obviously makes it easier to consistently identify the characteristics that are unique to the individual, such as name and date of birth, while also easily identifying the appropriate evaluation elements, like grade average, graduation date, and school. These elements vary from country to credential, which is why it’s so useful to focus initially on a single country or single credential when you’re first starting out. I’ve included a sample of the contemporary Bang Tot Nhgiep Trung Hoc Pho Thong, or Graduation Diploma from General Upper Secondary Education, from Vietnam that has been awarded in this format since 2008/2009.

This credential from Vietnam is a good choice because it has all of the elements designed to make it straightforward to “read” the native language diploma: an alphabet similar in appearance to my own (other than the diacritics) since the Vietnamese alphabet uses the Latin script; a national document prepared by the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) and specific to the range of years issued; and obvious blank space for filling in the student-specific information. Once I learn the bare bones for this standardized document, I can apply that information to all others from the same time period and easily hone in to identify – and validate – the student-specific information. By understanding the elements in this native language document, I am able to rely less on the translation and focus more on the actual documentation provided. If your attention is on the translation, it’s very easy to miss when the expected elements don’t appear on the native language documents, when documents don’t seem to match the appropriate format for the time period, when common anti-fraud security features aren’t there, etc. In Vietnam, secondary school documents are all issued by the appropriate regional department of education on the same MOET-provided document so there’s a lot of consistency or continuity. At the higher education level, there is still a great deal of standardization, but growing numbers of institutions have flexibility in their documentation practices. Of course, this standardization typically refers to the graduation credential only, so the transcripts themselves may be a free-for-all.

Learn to Read Common Terms

However, once you have mastered reading the elements on the native language diplomas and degrees, you will start feeling more comfortable looking at the native language transcripts and identifying and seeking out the commonalities found there, too. It’s only a short step away until you’re comfortably reading the key elements of the native language documents for a variety of languages and countries. Other countries that have standardization in their graduation documents include China, Iran, France, Russian Federation (and many of the former members of the Soviet Union), Bulgaria, and Romania. In addition, many countries award a standardized national leaving certificate upon completion of secondary schooling, like Ethiopia, the members of the Caribbean Examinations Council, Nigeria, Haiti, Italy, Cambodia, Jordan, Egypt, Hong Kong, Iraq, Rwanda, Algeria, Mongolia, and South Africa, among others. In addition, other countries may issue a specific national standard high school diploma and/or transcript rather than a leaving examination certificate that still follows a common format, including Turkey, Afghanistan, Peru, Greece, Saudi Arabia, Canada (specific to province), and more. None of these are all-inclusive lists but simply a short set of examples to show you that much can be gained from attempting to learn to identify the patterned elements of native language documents.

In addition to learning to read patterns in the graduation credentials, it’s also important to learn to recognize the names of the credentials, the types of degrees or categories that are typically awarded, and other important terminology. This helps you look for the important elements on the academic record or transcript, which is less likely to be issued in a uniform format. Some of the most useful terminology includes words like duration, examination, grade or marks, minimum pass, career or field of study, full-time or part-time, education level, semester, class hours, subjects, average grade, and a number of other terms that may vary by education level and country. In some countries, degrees are only offered in certain fields, and being able to recognize them helps to identify problematic documents. On the other hand, in some countries, different documents are issued for incomplete or in-progress studies, so what may appear as an unofficial record may actually just be non-standard but totally legitimate. In addition, sometimes unofficial records, like notarized copies, may have more stamps, embossed seals, or ribbons than their official counterparts.

It is incredibly helpful to maintain a country- or language-specific list of common terms in the native language to assist you in reading the documents. It is also useful to maintain a list of popular subjects; this is especially important (and easy!) for countries that have a national leaving examination or a series of mandatory undergraduate courses that must be completed by all students. I’ve included some starter resources at the end of this article, but you will find that many of the resources listed in previous installments in this series on building your resource library also include translation information.

Learn to Read Numbers

Reading the numbers on the native language documents is another integral step. It’s easy for even the most professional translators to make mistakes in typing grades or units associated with a course. Even if you find that the particular font or handwriting of the graduation diploma, course names, and even the rest of the document is beyond your skills, reading the numbers is often much more straightforward. Many alphabets use a variation of the Latin script of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system.

| Latin Script | Chinese | Arabic | Persian | Hebrew |

| 0 | 〇 | ٠ | ٠ | |

| 1 | 一 | ١ | ١ | א |

| 2 | 二 | ۲ | ۲ | ב |

| 3 | 三 | ۳ | ۳ | ג |

| 4 | 四 | ٤ | ۴ | ד |

| 5 | 五 | ٥ | ۵ | ה |

| 6 | 六 | ٦ | ۶ | ו |

| 7 | 七 | ٧ | ٧ | ז |

| 8 | 八 | ٨ | ٨ | ח |

| 9 | 九 | ۹ | ۹ | ט |

Keep in mind that even in alphabets that are written right to left, like Arabic and Chinese, numbers are still written left to right. It’s also useful to note that some documents may include a combination of Latin Script numbers in some parts of the documents and native language numbering in other places. In China, for example, transcripts usually list grades and hours or credits using the Latin numbering system, but graduation dates, start and end dates, dates of birth, and other dates are often written using Chinese numerals.

In addition, calendar dates are written day/month/year in most of the world, but parts of North America tend to use month/day/year models for dates. Some countries like Iran and Nepal use their own calendar dating that appears on the documents, and that information needs to be converted as well. Happily, the internet is a wonderful resource for identifying online date converters.

Learn to Read Grades

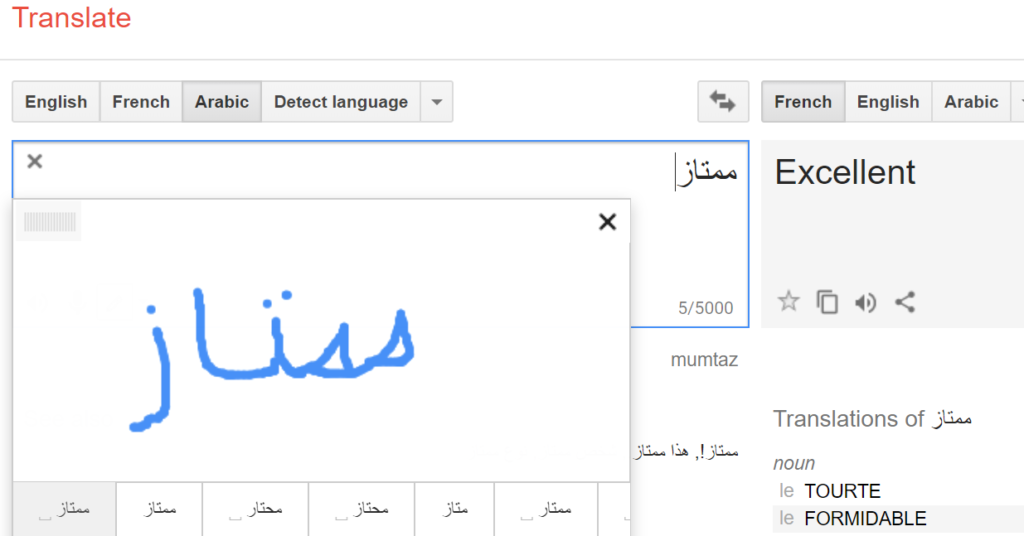

An important – and often easier – part of reading native language documents is reading the grades. Even countries that don’t award documents on a Ministry-designed credential or have regulated degree categories may be inclined to use similar grading ranges. Obviously, if the grades are written on the native language documents in numbers, then this element doesn’t apply, but a large number of educational systems award descriptive, or verbal, grades. If you’re not familiar with that terminology, a descriptive or verbal grade simply means that the institution awards grades in the form of a word or phrase rather than numerical or letter grades. Common descriptive grades include Excellent, Good, Average, and Poor. Examples of countries with descriptive grades include France, Russian Federation, Mexico, China, Egypt, South Africa, and Australia. Some countries, like China, include a combination of numerical grades and descriptive grades.

In other countries such as Mexico, India, and Egypt, different faculties within the same institution may use numerical grading while others use descriptive grades. I’ve included a short chart that includes some common verbal or descriptive grades.

Please note that the chart below is NOT intended as a crosswalk across grading systems. A grade of Хорошо (Good) in Russian is not comparable to a grade of Tres Bien (Very Good) in French. This chart is simply to show some of the more common descriptive grades in use and rough approximations of their translation but is not meant to imply that they are equivalent grades from one language or system to another.

| English | French | Arabic | Russian | Chinese | Spanish |

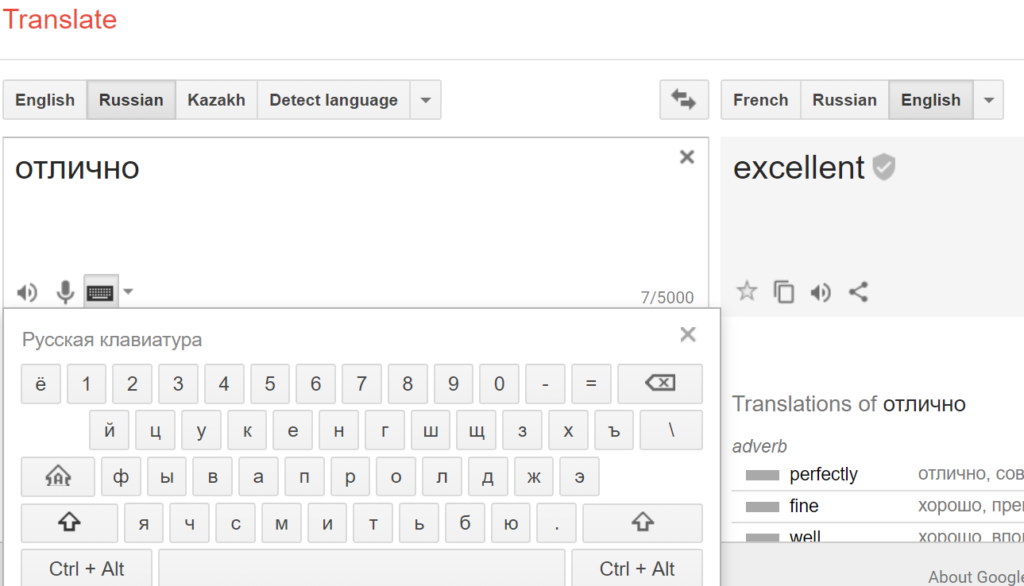

| Excellent | Excellent | ممتاز | Отлично | 优秀 | Excelente |

| Very Good | Tres Bien | جيد جدا | 良好 | Muy Bien | |

| Good | Bien | جيد | Хорошо | 中等 | Bien |

| Satisfactory | Assez Bien

or Passable |

قبول | Удовлетворительно | 及格 | Regular or Suficient |

| Poor/Failed | Ajourne | مردود | Неудовлетворительно | 不传 | No Suficient |

| Passed | Зачет | 合格 or 通过 | Acreditada |

Again, the chart above is meant only to highlight some of the more common descriptive grading systems and the importance of being able to read them in their native language. Even the most well-intentioned and professional of translators may use a different translation for a particular term than you use in-house, and it’s easy to convert grades inappropriately if you rely on someone else’s translation.

Now that we’ve identified what needs to be done in order to increase your reliance on the native-language documents themselves, how do you learn all of this? Are you expected to become fluent in ever written language in addition to all of the continuing education you need to learn the educational systems themselves? There are a number of strategies that you can employ to facilitate the process of using the native language documents themselves in your evaluation work. You can compare the translation you receive to your in-house glossary and then compare that to the native language document to ensure the translation makes sense. This allows you to validate your confidence in the translation that was provided if you are not doing the translations in-house. I’ve included some resources at the end of this article to help you build or grow your in-house glossary tools.

You can also look up the indigenous terms in your glossary or language dictionaries. This is obviously easier to do when using the same or similar base alphabet, but some glossaries or dictionaries are also organized by topic. In addition, the more time you spend looking at another alphabet, the more you start to identify unique letters or characters, and the easier it is to work with source material in the native language.

Another fun strategy is to use Google Translate with the obvious caveat that it should be used as one tool in your translation toolkit but not as a replacement for a professional translation from a certified translator. However, it’s great for spot-checking translations and growing your in-house library. One of its many neat features is that you can use a handwriting feature to (try to) recreate the native language terms. This is not available for all languages, but I personally use the Arabic and Chinese handwriting options on a regular basis. If it’s available for that language, you simply select the pencil icon after selecting the native language. If the handwriting option is available, you will use your mouse (or digital pen if you’re fortunate enough to have a smart stylus) to write your best effort. Google Translate will offer suggestions at the bottom of the drawing screen of what it thinks you’re trying to write.

For some languages, however, it’s easier to type the letters. Instead of having to install a language pack and learn the keyboard shortcuts for creating the various characters or letters, Google Translate itself provides a virtual keyboard. This onscreen keyboard allows you to easily type the native language characters to figure out if your translations are roughly accurate. Remember, this is an electronic tool and not a skilled person who is translating the terms within the context of the educational document. However, I often find that recreating terms using the virtual keyboard is the fastest way to identify the native language spelling of the institution, which frequently makes it much easier to look up the institution’s recognition, which might not always match a list of recognized schools in your language. In addition, some countries offer online verification portals that may require personal data such as student name, and using a virtual keyboard can be much easier than trying to find the characters that make up a person’s name.

Just as the English language has different fonts, handwriting, spelling variations, and cases (upper and lower case) so do many other languages. You may think that have the wrong word, or your translation is suspect because things don’t match up, but you may be dealing with simple variations that seem like totally different words but aren’t.

Often, copying a native language term from Google Translate and then putting that word in italics can make it clearer that you’re dealing with the same word. As an example, Отлично, Отлично, Отлично, and Отлично are all the same word but in different fonts and styles. To put it into perspective, remember that many words in English look completely different in type versus script, and you might realize how easily it is for the same word to look completely different.

Obviously, there is a learning curve, and you will get stuck. That’s why you should still require a translation. Your goal here isn’t to replace the translation with your own abilities. Your goal is simply to conduct as much of the evaluation work from the native language documents as possible. And the amount of work you do from the native language documents will grow over time as you become more familiar with the different alphabets, grow your in-house glossaries and libraries, and become less overwhelmed at this seemingly enormous task.

Where should you start? Look at the documents you receive. If you don’t get Vietnamese high school graduates, then that’s probably not the best starting point for you. On the other hand, if you see a lot of Chinese documents crossing your desk, then learning how to identify the patterns on their graduation credentials and beginning to look for key terms on the transcripts should be a high priority for you, even if you’re requiring verification from CHESICC or CDGDC (which I highly recommend). If you’re trying to grow your program with students from a particular country or language, it’s an excellent idea to spend some time familiarizing yourself not just with their educational system but with the native language documents, alphabet, and key terms.

If you’re interested in learning more about translations and adding more samples to your sample library, I am scheduled to present on this topic in Philadelphia during the 2018 TAICEP Annual Meeting from October 1-4. The session will include samples and translation glossary information from credentials issued in French, Spanish, Vietnamese, Chinese, Cyrillic, Arabic, and Persian. These languages represent the six official languages of the United Nations as well as some of the countries that are increasingly sending their students abroad.

I’ve included a short list of some of the resources that you can use to build or grow your resource library with respect to translations. These are multi-country resources, and some of them require a membership or login to access them, but most of them are freely available online.

IERF Index of Educational Terms: http://www.ierf.org/for-institutions/ierfpublications/index-of-educational-terms/

QQI NARIC Ireland: http://qsearch.qqi.ie/WebPart/Search?searchtype=recognitions

CEDEFOP: http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/node/11730

IQAS International Education Guides: https://www.alberta.ca/iqas-educationguides.aspx

AACRAO EDGE: http://edge.aacrao.org/aacrao-edge-loginpage.php?uri=/

Australian Department of Education and Training: https://internationaleducation.gov.au/CEP

NAFSA Guide to Educational Systems around the World: https://www.nafsa.org/_/File/_/guide_educational_systems_2005.pdf

NUFFIC modules: https://www.nuffic.nl/en/diplomarecognition/foreign-education-systems

European Glossary on Education, Vol I-V: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publicationdetail/-/publication/6dc168d4-7a44-4a90-a247-4300e9769e47/language-en

Classbase: https://www.classbase.com/Countries/Armenia/Credentials

RecoNow: http://www.reconow.eu/en/index.aspx

Eurydice: https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/nationalpolicies/eurydice/content/glossary_en?2ndlanguage=

San Francisco Public Schools: http://www.sfusd.edu/en/assets/sfusdstaff/services/files/translation-interpretationglossary.pdf

Palm Beach Schools: https://www.palmbeachschools.org/multicultural/wpcontent/uploads/sites/70/2016/04/TranscriptGuide.pdf

Everett Public Schools: http://docushare.everett.k12.wa.us/docushare/dsweb/View/Collection-6395 Collier County School District: http://old.collierschools.com/ell/docs/Translation%20Binder.pdf

Transcript Research Glossary of Foreign Terms: www.transcriptresearch.com/translations.pdf

In this Edition:

Organizational Updates -May 2018 Newsletter

Member Spotlight: Grant Adams A New Home in Credential Evaluation -May 2018 Newsletter

EQPR Project -May 2018 Newsletter

Building a Resource Library Part IV: Translations -May 2018 Newsletter